All Seasons Blog

Kind Kids, Strong Communities

Encouraging our class to treat each other with kindness, to offer a helping hand, to notice when someone is out of sorts, to forgive, and to acknowledge mistakes or regrets teaches them what kindness looks like and feels like. They are some of the most worthwhile lessons we learn in preschool.

Building Community Day By Day

Community in a preschool classroom isn’t something that just happens; it's something we build together, day by day, through small acts of care and connection.

You Are Doing Great: A Positive Letter to All the Parents

Dear parent of a young child,

Parenting young children is both a beautiful and demanding journey, and I want to take a moment to acknowledge the love, patience, and effort you put into raising your children each day.

Building Oral Language at Home and School

If we want to raise strong readers, children first need to have a strong oral language foundation. Simply put, the more words a child knows the easier it will be for them to learn to read and write when they are ready. This is why in the Autumn Room at Eagan we intentionally encourage conversations throughout the day.

Little Learners, Big Adaptations: How Toddlers Learn to Thrive in New Seasons

At the beginning of the year, many children arrived holding tightly to their grown-up’s hand, unsure of what the day might bring. Yet, day by day, we’ve watched them adapt. They begin to recognize their teachers as trusted caregivers, find comfort in familiar classroom rhythms, and build relationships with their peers through play, laughter, and even the occasional disagreement. These moments, both joyful and challenging, are all part of how children learn to navigate the world.

A Seat At The Table: Making Room For Elderly Adults At Our Family Gatherings

This was my realization: people - myself included at one time - have become accustomed to relegating older people to the isolated and blurred edges of social events and we don’t even realize we’re doing it. It’s through working at All Seasons, and interacting with seniors on a regular basis, reacquainting myself with their humanity, holding my mother’s hand as she enters this chapter of her life that I’ve become more aware of it. I know that no one in my family, any family, would do this intentionally. I thought I’d share the list of ways to include and connect with the elders in my family in hopes that you are inspired to find ways to do so in your own holiday gatherings.

Learning and Growing Together in Mixed-Age Classrooms

One unique aspect of our program at All Seasons Preschool is our use of mixed-age classrooms. Instead of separating children strictly by age, we group 3-, 4-, and 5-year-olds together. This is an intentional choice grounded in research and experience.

One Magical Monkey

As someone who has had careers in theatre and early childhood education, I’ve seen firsthand the marvel and wonder puppets bring to children. Puppets are magical catalysts for storytelling, providing a physical anchor to imagination. To children, they are real beings who ignite joy.

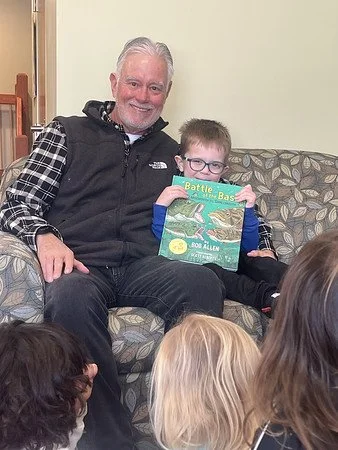

Better Together

There is something truly remarkable about the energy created when multiple seniors come to visit the preschoolers on their own territory at the Open House. The children have more confidence and comfort - this is their space, after all! - and as the experts, they gleefully show the seniors around, introduce them to their favorite toys, and ask, without much hesitation, for them to read a book on the sofa. The energy the seniors bring with them is pure enthusiasm. They come prepared to ‘oooh’ and ‘aaaah’ over the children, the classrooms, the activities, and the trinkets, art projects, and playdough creations the preschoolers bring them. It is a special thing, and it serves both populations beautifully.

Joy In The Little Things

“The magic in your childhood wasn’t because you were a child. It was because you were living in the present.”

The Heart Of All Seasons

The impact of preschool on a child’s future education has been well documented. But what about the impact on their hearts?

This year, two of my former students returned to All Seasons, one to inspire preschoolers in the Art Studio, and one to visit the senior residents and their old classrooms…

Not A Child, But YOUR Child

Our teachers know young children. They will know their class as a group. Most importantly, our teachers will know your child.